How to use USWDS

How to track performance

A step-by-step guide to picking metrics and tools for tracking performance on your site.

Introduction

Tracking your site’s performance is the first step to incorporating performance into your design and development process. This guide will take you through the steps in tracking performance. It can be used on an existing site or a new site. In this guide, we’ll go over:

To make the guide easier to follow, we’ll be taking an actual site, dashboard.cloud.gov, through the entire process. The dashboard is a user interface for the cloud.gov platform, which allows government agencies to launch servers and sites with ease in the same vein as private products. Throughout this guide, we’ll use callouts like the one below to highlight specific examples:

Example

Examples will be displayed in a box like this.

What you’ll need

Before starting this guide, it’s important to define some basic information, which will make it easier to choose metrics and tools. If the site is in an early discovery mode, and your team is unable to answer the majority of the questions below because various aspects of the site architecture and content haven’t been decided yet, it may be too early for this guide. Attempt to define, as best as possible, the following information:

Is there an aspect of your site’s experience that’s more important than the rest? An example is, “How fast does a tweet show up on Twitter?”

Example

For the cloud.gov dashboard, being able to see the status of a running application is a very important experience.

Is the primary user interaction more passive, such as reading content, or dynamic, such as updating, creating or modifying data?

Example

For the cloud.gov dashboard, the interaction is dynamic. The user is mostly clicking and taking actions on the page.

Is the site currently, or will be, a Single Page App (SPA), where the page routing and interactions are all done through client-side JavaScript, or a more classic server-response architecture?

Example

The cloud.gov dashboard is built with client-side React code with all client-side JavaScript routing, so it’s an SPA.

Is the site only accessible through some sort of authentication, or is it a public site? Does the site currently have, or will have, a continuous integration (CI) service setup? Does the site have automated testing that runs on the CI?

Example

The cloud.gov dashboard uses a CI services where tests are run for every build.

How often does the site release new versions?

Example

The cloud.gov dashboard releases about once a week.

What are some comparable sites or services to the current product?

Example

Heroku, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Azure, Pivotal Web Services, and IBM Bluemix are all comparable products to cloud.gov.

Once this information has been defined and written down, the team is ready to start choosing tools and metrics.

Choosing metrics & tools

Deciding which metrics to track is one of the most important parts of performance tracking. Performance metrics are various indicators for how fast the site is performing for your users. This section of the guide will go through the process of choosing the best metrics for your site. Your team can also use our suggested default metrics and tools, which work for the majority of sites, if you’d prefer to not go through this process. This information can be found at the end of this section.

Choosing metrics

Different performance metrics reveal different things about the experience a user has on a site. In order to make the process of choosing metrics easier, we’ve compiled a large list of performance metrics and detailed each metric’s pros and cons. It’s important to choose at least one primary direct metric and at least one primary indirect metric. Attempt to track at least three metrics. There is no limit to the total number of metrics you can track. It depends on your team and what metrics help the most in determining performance. It’s also important to consider HTTP/2 when deciding metrics. See our HTTP/2 guide to learn more about its impact on performance.

Example

In the cloud.gov dashboard, we have chosen the following metrics:

- Speed index: It’s a great way to compare sites and a good default.

- Time to interactive: The dashboard is a very interactive site, so we want information on how easy it is for the user to interact with the site.

- Input latency: The dashboard is an SPA, so the time it takes to move between various pages and show various UI is very important.

- Custom timing events: Viewing app stats is a very important part of the experience.

- Frontend / backend time: It’s helpful to see where the bulk of the site’s rendering time goes.

- Page weight: The dashboard is an SPA, so page weight can quickly get out of hand if new JavaScript libraries are added.

- DOM nodes: As a React app, there could be many DOM notes created that we don’t realize, as React is in charge of actual DOM rendering.

Choosing a tool

Once you’ve decided which metrics your team wants to track, you’re ready to choose a tool to accurately track these metrics. Different tools can be run in different ways and show different metrics. When selecting a tool, it’s important to consider what metrics the tool reports on and how the tool runs.

Checking chosen metrics

The first step in choosing a tool is to make sure the metrics you chose before are reported by the tool. To simplify the researching process, here’s a small helper to determine which tools track which metrics. To use it, select the metrics you plan on using from the dropdown lists and view the chart below to see whether it’s available in each tool.

Depending on the metrics you’ve chosen, it might be difficult to find a tool that tracks all of them. If you’re finding that it would take more than three tools to track all your metrics, it might be time to go back to your chosen metrics and take some out that are harder to track. When doing this, it’s usually wise to leave in the primary direct metrics, such as Speed index, but take out some of the secondary direct metrics, such as onload or first byte.

It is possible to use two different tools to track all your metrics, but not recommended. Using more than one tool will require your team to merge the data from the two separate tools in a way that is parsable and makes sense, which could increase complications down the road.

Checking how the tool runs

Besides checking that the tool tracks most of the main metrics your team is interested in, it’s also important to consider how the tool will be run. The following scenarios show why certain tools are better based on the conditions of the site and the team:

- If the site is not public and you have to login to use it, performance tools that can be run in the browser, such as Google Chrome Lighthouse, make the process of testing much easier. Otherwise tools have to be configured to login to the site in an automated fashion, or have login cookies set up so the tool can access the site.

- If your team doesn’t use the Chrome web browser, then using Sitespeed.io as a tool is a great choice. It reports on most of the same metrics as Lighthouse but doesn’t require a particular browser.

- If your team has limited ability to install the Chrome web browser, Chrome extensions, or CLI applications, then webpagetest can be run in any browser and is a good option.

Example

In the cloud.gov dashboard, we decided to use Google Chrome Lighthouse. Google Chrome Lighthouse reports on most of the metrics we’re interested in and is able to run in both CLI and as a browser extension. Since the dashboard isn’t public, and you need to be logged in to use it, Lighthouse’s ability to be run in the browser makes testing the site much easier.

Some defaults

Not all sites require an extensive process to choose performance metrics. Many sites can use these recommended defaults and achieve valid tests.

Default metric recommendations:

- Speed index: a direct metric to track how fast a site appears to a user

- Custom timing events: a direct metric to track a specific experience on your site

- Page weight: an indirect metric to track the total resources size to download for your site

Focusing on these three metrics provides a good overview of how well your site is performing and allows you to compare your site’s performance to other sites.

Based on these metrics, we’ve also recommended tools that are able to track these three metrics.

Default tool recommendation:

Google Chrome Lighthouse: a Google Chrome library that can be run in the CLI or as a browser extension. Google Chrome Lighthouse can be run in a CLI, or developer environment. It’s relatively easy to set up, and use, and includes harder to track metrics, like Speed index. Its only downside is that it requires both the Chrome browser and the ability to install Chrome extensions. If your team is unable to install Chrome or Chrome extensions then webpagetest can be run in any browser and is a good option.

Once you have chosen metrics and a tool to track the metrics, the next step is to define your performance goals and potential budgets, or limits, for the project.

Setting budgets & goals

Tracking performance can become a useless endeavor if nothing is ever done with the data. Setting performance budgets and goals ensures the team has a constant view of the site’s performance. Budgets are limits you place on the team for performance. A budget can be set for each, or every metric, and will tell the team that the metric can’t go above or below a certain amount. Teams often incorporate their budgets into their build process so if a certain code change goes over budget, then the tests will fail and the code change has to be re-thought. Goals are more long-term idealized budgets. Goals are only required for existing sites where the current speed is far below the desired speed. Goals can also be set for each metric, and serve as a prod for the team to keep improving performance.

Comparing speed with other sites

The first step in setting budgets and potentially, goals, is to have an idea of how your site should perform compared to similar products or services. In private industry, these would usually be competitor sites. In government, any sites that roughly compare to what your product is trying to accomplish, works for comparison. We’ll use the products defined earlier to do comparisons.

The best way to do comparisons is to run your preferred tool(s) against each chosen comparison site. To do the comparison, your team should choose three to six comparison sites to run testing against. The tool should be run against one to three pages from each comparison site, based on how different each page is from one another.

- To do this in Google Chrome Lighthouse, visit one to three pages for each comparison site, run the Lighthouse extension, and export the results. Lighthouse also has a secondary tool, lighthouse-batch, to run against multiple URLs to make this process faster.

- A similar process can be used for Sitespeed.io by running the CLI command for each page of each comparison site. Sitespeed.io also has an option to run against multiple URLs, similar to lighthouse-batch, built into the actual tool.

Once all the data is collected for each page, of each site, you’ll want to compare the data and get an idea of the max and min values for each of your chosen metrics for each site. It’s up to you how you want to do this. One way is to make a Google spreadsheet comparing each metric to each site page.

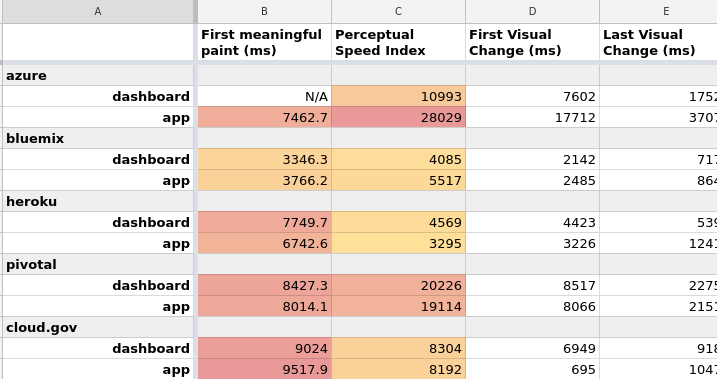

Example

In the cloud.gov dashboard, we used Google Chrome Lighthouse to test against four comparison sites: AWS, IBM Bluemix, Pivotal, and Azure. For each, we ran a test on the landing page and a specific app page. We saved all the results and created a spreadsheet in Google documents alongside our own Lighthouse test on cloud.gov. We also included results from our own cloud.gov dashboard.

Choosing budget and goals

Once your team has data on each metric, for each comparison site, and metrics on your current site, if it exists, you’re ready to set budgets and goals. To reiterate, budgets are limits you’re placing on your team within the design and development process to ensure performance doesn’t get worse while the site is being built. Goals are only required when your existing site’s current performance is much slower than your desired budgets of where you want your performance to be.

Selecting budgets for a not yet built site

A good idea for selecting budgets is selecting the fastest performing site for each metric and taking 20% off the value. We use 20% because a 20% time difference is what’s often required for a user to see a difference in performance. This means we’re looking for our budget to be noticeably better than the best comparable site. For example:

- The Speed index for our four test sites were: 10993, 5517, 19114, 4085.

- The lowest value, or minimum, is 4085.

- We’ll take 20% off that value for a Speed index budget of 3268.

This value can also be compared to the recommended values from your tool. Google Chrome Lighthouse provides a target value for each metric. If the budget is far off the target, it might be a good idea to bring it closer to that target. You can also round the numbers up or down to make them easier for the team to remember.

Not all metrics require setting a budget. Any metrics that can’t be compared, such as Custom timing events, should not have a budget. Other budgets are simply a yes or no value, such as whether the site is mobile friendly, which doesn’t require a budget. Additionally, it’s up to your team to analyze the data and set budgets for what makes sense.

Selecting budgets and goals for an existing site

Selecting budgets for an existing site is similar to selecting for a non-existing site, but the current site’s performance has to be considered. To start, calculate the minimum value for each metric and subtract 20% from each, as described in the section above. Once you have the minimum 20% value, compare it to your current site’s performance in each metric.

If your current site’s metric is better than the minimum 20% metric, you can set this value as the budget and the goal for the metric. If your current site’s metric is worse than the minimum 20% metric, the value should be set as the metric goal instead of the budget. The budget should be set to the current site’s value.

This ensures that your site currently passes the budget, but the team is aware of goals to move towards. Budgets are meant to stop performance from getting worse. Goals are meant to push performance to get better.

Again, not all metrics require a budget, it’s up to your team to analyze the data and set budgets for what makes sense.

Example

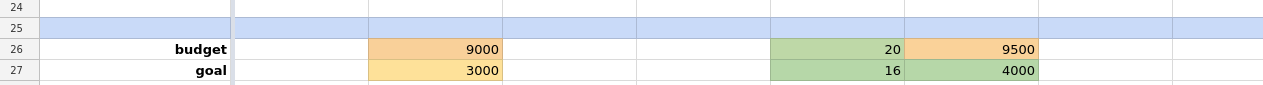

In the cloud.gov dashboard, we set the following budgets and goals:

- Speed index

- Budget: 9000ms

- Goal: 3000ms

- Input latency

- Budget: 20ms

- Goal: 20ms

- Time to interactive

- Budget: 9500ms

- Goal: 4000ms

- Page weight

- Budget: 2000 KB

- Goal: 1000 KB

- DOM nodes

- Budget: 1500

- Goal: 1000

For Speed index, Time to interactive, and Page weight, our current site’s performance was worse than the minimum 20% value, so these metrics required a budget that was closer to where the current site was- and a future goal of where we wanted it to be. Input latency and DOM nodes were lower than the minimum 20% value, so we allowed ourselves some room to grow here. We also bumped the numbers to round them.

If your metrics have a large gap between the budget and goal, it might be wise to narrow that gap a little in the short term so progress is more easily measured. Having a goal also means the team should be made aware of it and how to get to the goal. We suggest discussing the goal in sprint reviews and retros, or providing “Performance days,” or sprints, where the team can all work together to improve performance.

Adding site tracking

Once you’ve determined the metrics to track, the tools to use, and what your performance budgets and goals are, it’s time to set up the systems to do the actual tracking of your metrics. How and when to track is up to your team and workflow. It’s a good idea to have a discussion with the team about the how, when, and what of performance.

- How do people want to hear about performance?

- Through what channels do they want to be notified?

- When in the development and design process do people want to be notified, or interact, with performance?

- What performance information do people need to feel they can influence but still get their job done?

In this section, we’ll discuss a few of the many ways to track web performance on a team. It’s up to your team to figure out which of these methods, or other methods, work best to track performance. When choosing, it’s important to remember the goal of tracking, as defined in the why track performance section, is to ensure all team members are aware of performance degradations and to motivate people to continually improve a site’s performance. For more information on different types of performance tracking, see the Types of monitoring methods in the glossary.

Methods of tracking

Continuous Integration

Tracking performance through a new, or existing, Continuous Integration (CI) service can often be the cheapest and most robust tracking method. Usually tracking on a CI is more geared to the developer team, but all team members can access the information on the CI and incorporate it into their workflow.

What you’ll need:

- A continuous integration server or service, which is able to run your site’s build at certain points during code changes. Some example free services include CircleCI or Travis CI.

- A build process that can run your website in a local, real or test environment, so that it can be visited at a localhost or staging URL

- The ability to add new tools to be run during your continuous integration build

Pros

- See speed changes at a very early part in the code release process, before it makes it to the live site

- Can block code from going to production that would cause large speed slowdowns

- Can run in multiple environments, like dev or staging

Cons

- Harder to involve the full team in site performance tracking

- Don’t know if simulated environment in build is close to what real users are experiencing

Real-time User Monitoring Service

Real-time user monitoring (RUM) is the only performance tracking method that allows you to see true performance measurements from users, getting your team to a closer understanding of how they experience the site. There’s plenty of information about RUM monitoring in the glossary. There are also costs and benefits to this solution.

What you’ll need:

- Ability to add a JS script to your site to track performance

- A paid backend service provider or manual backend service to collect performance data. An example service is SpeedCurve.

Pros

- The most accurate measurement of what users are experiencing

Cons

- Not possible to measure important metrics, such as Speed index, first meaningful paint, input latency

- Requires many users to see useful data, more than 500 uniques per day

- Requires a backend service running, so is the most expensive option

Content Management Solutions

A Content Management Solution (CMS) tracker should only be used if your site has a CMS, and your research has shown that the majority of performance issues relate to content being updated in the CMS. This solution will track and report on performance during the CMS content editing process.

What you’ll need:

Pros

- Can alert users that may not be as familiar with performance when they’re writing CMS content that has performance implications

- Only reports performance when things in the system could change

Cons

- Lack of tools in CMS performance tracking, so relatively hard to configure

Depending on how often the code of the site gets updated, the team might need two tracking solutions: one for the CMS and one for the code updates, leading to a more complicated system.

Example

In the cloud.gov dashboard, we decided to do CI testing because we already had a reliable CI setup and the team is primarily made up of developers, meaning CI would be where performance gets the most attention. We set up Google Chrome Lighthouse in our build process, ensuring that if a recent code change goes over budget, it would stop the build and report the problems to the developers. Additionally, we used a Github service to receive performance reports over time.